A Retired OB/GYN’s Guide to Helping Black Mothers Survive

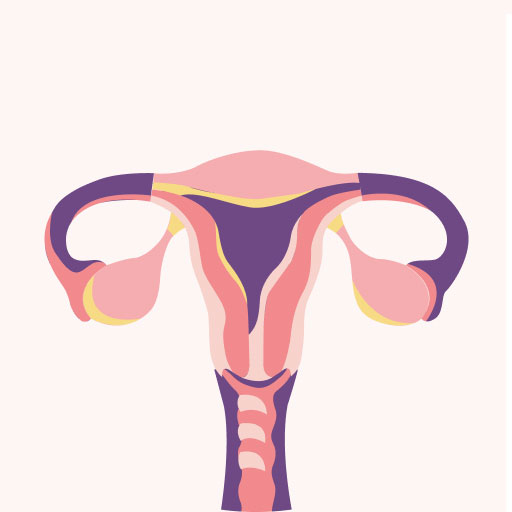

I am a retired physician from New York with 30 years of experience in obstetrics, gynecology and female reproductive health. In retirement, I am focused on eliminating racism in medicine and finding solutions that the Black community can use to obtain person-centered and supportive care. My search for those solutions led to the founding of the Black Coalition for Safe Motherhood (BCFSM).

The journey from a career in medicine to addressing racism in medicine and healthcare services began long before I thought about attending medical school. As far back as I can remember, racism was part of the conversation in my family. My parents were an interracial couple when that was a rare, head-turning phenomenon even in New York City. My dad was handsome, dark skinned, proud, and ready with an angry response for those who stared at him and Mom, or made racist comments to him at the post office where he worked. My mom was a blue-eyed Brooklynite, fearless and daring to hang out with Black and Jewish people in the early 50’s. They both were defiantly ignoring their families’ warnings about the difficulties and dangers they would face when they married in 1954.

By 1960, four children in four shades were born to my parents, Joan and Duane. They used Joan’s white privilege to get home loans and buy everything from cars to Christmas trees to shoes for the children. Even though he had not graduated from high school, Duane sought to educate the family about what was known then as Negro History. Racism, the civil rights movement, and the economics of oppression, were part of every day discussions in our household. My dad included me in the adult conversations from the age of 12. I read Malcom X, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin. When we traveled to my uncle’s wedding in South Carolina, my mother drove separately with me in our car. My sister and father rode with other family members. Incidents like that, in addition to the upheaval of the 1960s struggle for equality, instilled in me a deep-rooted passion for racial justice and a sensitivity to not being recognized as a Black person.

In college, I insulated myself within a close knit group of Black students at Johns Hopkins University during the early 70’s. I wound up marrying someone in our group, a pre-med student from Baltimore, and quickly became pregnant with my first child.

Nine months later, I was cared for by a student midwife at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The nurturing support she provided during labor and birth was transformative. I decided that day to become a midwife. Lacking confidence in the employability of midwives at that time, my husband insisted I would be better off going to medical school and becoming an obstetrician. And so, I went on to give birth to two more daughters, then transitioned from being a homemaker to attending medical school at Howard University College of Medicine. I then completed my OB/GYN training at Long Island Jewish Medical Center in 1989 and practiced obstetrics there for 20 years.

During that time, I was a deeply caring and trusted clinician who emulated the midwifery model of care. That said, the challenges of my studies and training distracted me from looking closely at the myriad ways racism showed up: from the photos of mostly brown skinned people’s genitalia in a class on STD’s to the disparaging comments of white nurses about patients of color in the Labor & Delivery Unit. I was preoccupied with my workload and the stress of raising a family in a difficult marriage. And, like most other doctors, I had picked up the habit of blaming patients for poor outcomes because they were noncompliant or poor historians. During most of my years in practice, I did not generally take the time to identify myself as Black or call someone out for racist remarks except in the rare incidents of overt racism.

My awakening to systemic racism in healthcare services began with my introduction to patient safety and preventable medical error in general. My own mother died from poor medical care after a car accident. My father became paralyzed because of delayed diagnosis. I was alarmed when I learned how common medication errors were, that doctors’ diagnoses were wrong about 10% of the time, and that almost 100,000 people per year died from healthcare related infections – most of which could be prevented if only all hospital staff would wash their hands.

As I became more aware of deficiencies in delivery of healthcare services to all, I decided to open my own independent practice of Gynecology and Well Woman Care in 2009. I aimed to have the time needed to communicate effectively with each person and avoid mistakes in their care. In 2009, I also joined Pulse Center for Patient Safety Education & Advocacy (CPSEA) to educate the public regarding the patient and family’s role in reducing preventable medical errors, and to raise awareness that the most important part of “caring” for health “care” providers should be listening to and centering the patient.

In 2014, I represented Pulse CPSEA as the community organization on the National Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. The Council was formed to address the high rates of pregnancy related deaths and near deaths in the United States.

It was at one of our meetings that I had my ‘aha’ moment around racism in medicine. First, I learned of the stark racial disparities in maternal mortality rates, and that 50-60% of those deaths were preventable. After further studies, I realized that mortality statistics are the tip of the iceberg of preventable harm experienced by the Black community due to racism in medicine and society. I finally recognized that the negative medical experiences and obstetrical complications which my own sisters had reported to me over the years were not isolated events of racial discrimination, but part of a widespread pattern of devaluation of Black women. Using my experience in the grassroots patient safety movement, and working with other Black women who were passionate about safety and respect in delivery of healthcare services, we began a community-based effort to find techniques and tools which expectant, intrapartum and postpartum mothers, as well as their families and supporters, could use to obtain safe, person-centered care with dignity.

Now, in sisterhood with the ACTT Family of midwives, obstetricians, doulas, nurses, educators, and community members, I am proud to launch the ACTT for Safe Motherhood Curriculum.

A.C.T.T.

Ask questions until you understand the answers

Claim your space – both physical and mental

Trust your body

Tell your story

The ACTT Family has formed the Black Coalition for Safe Motherhood (BCFSM) to spread the interactive and transformative ACTT Curriculum to Black Communities in cities, suburbs and rural areas nationwide.

BCFSM is dedicated to improving Black Maternal Health and Wellbeing through promotion of health care advocacy and holistic support of birthing people so that Black Families thrive, not just survive.

More Content

Pregnancy & Parenting

The Grit of Faith and the Safety of a Black Doctor's Face

It was the day after we buried...