Part 1: How PMDD Affects the Brain

Isolation. Stress. Cat allergies. That’s all it took for my carefully constructed house of cards to come crumbling down. I felt overwhelmed, and I couldn’t stop crying. I took a pill, then another. Then a few more. Half an hour later, my throat burned with the acrid taste of bile and half-digested hydroxyzine. My circumstances, while less than ideal, had not changed overnight.

On Wednesday, life sucked, but I was hanging in there.

On Thursday, I wanted to die.

On Sunday, I started my period.

That’s when everything clicked.

I have Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) with Menorrhagia (otherwise known as excessive bleeding). I’ve heard it described as PMS on steroids, but that definition doesn’t scratch the surface of what my life has looked and felt like since I was first diagnosed over a decade ago.

For the last six years, the length of my periods has increased, and the days between cycles have decreased. I now spend more days of the month on my period than off of it and my cycles bring a ton of symptoms, including vomiting, pain, fevers, hot flashes, extreme lethargy, and an inability to focus. Although the physical symptoms are awful, the impact it has on my mental health is even worse.

I’m irritable, anxious, and depressed.

I have severe suicidal ideation that starts three or four days before my cycle and lasts until day two or three of my cycle That’s how I got caught slippin’. My period came three days early, I wasn’t braced for the wave of hormone-induced suicidal ideation that typically precedes my menstrual cycles, and suddenly killing myself seemed like a completely reasonable response to ineffective allergy medication.

But I know that I’m not alone. Suicidal ideation is a fairly common side effect of PMDD. In fact, a qualitative review by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that people with this disorder are seven times more likely than their peers to attempt suicide. Given this alarming statistic, I spoke with nearly a dozen doctors, psychologists, and sexologists to better understand PMDD, and while I learned a lot about my body, I ultimately ended up with more questions than answers.

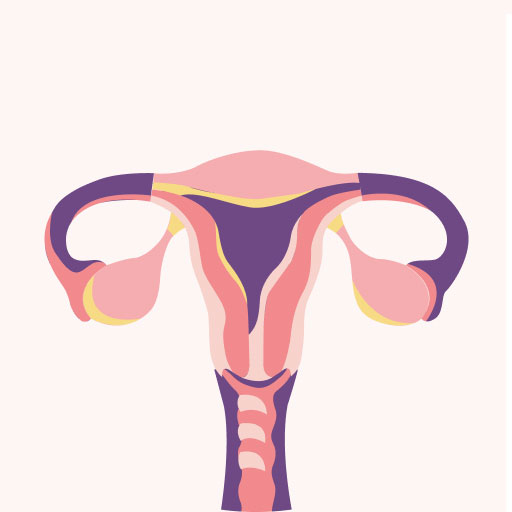

For instance, premenstrual dysphoric disorder is considered a mental health disorder according to the DSM-5-TR, but the way it affects your body complicates things. Sexologist Rhiannon John helped me understand PMDD’s onset happens during the luteal phase of menstruation–which occurs after ovulation and before your period–and usually wraps up just before or at the beginning of your period.

During the luteal phase, your body uses estrogen and progesterone to grow a memory foam blood mattress that’s perfect for a nine-month guest. If a fertilized egg ‘checks in,’ your body continues to create progesterone to keep that mattress nice and thick for a baby. If not, your uterine lining sheds, causing the bleeding we call our periods. Since I have two periods a month, my luteal phase is literally whenever I’m not bleeding.

Additionally, people with PMDD are more sensitive to hormonal fluctuations than their peers, so the sharp drop in progesterone levels can cause a drop in serotonin production, which leads to emotional symptoms like irrational rage, hopelessness, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation.

And I’m not talking PMS-level rage where it’s just one of those days–I’m talking barely stopping yourself from driving into a CVS while you scream, “Tamika is a filthy c***, and I hope she gets syphilis and dies!” I can’t even remember what I was so angry about, but I do remember the shame I felt later.

Sorry, Tamika…

So yeah, PMDD is definitely a mental illness, but it also comes with physical symptoms that a mental health provider alone might not be able to treat effectively.

Stay tuned for Part 2, coming soon!